Jerome P. Arbuckle

Celebrating Wisconsin Visionaries, Changemakers and Storytellers

An Ojibwe Woodland Storyteller

Storyteller | Jerome P. Arbuckle Bad River Ojibwe | 1911 - 1991

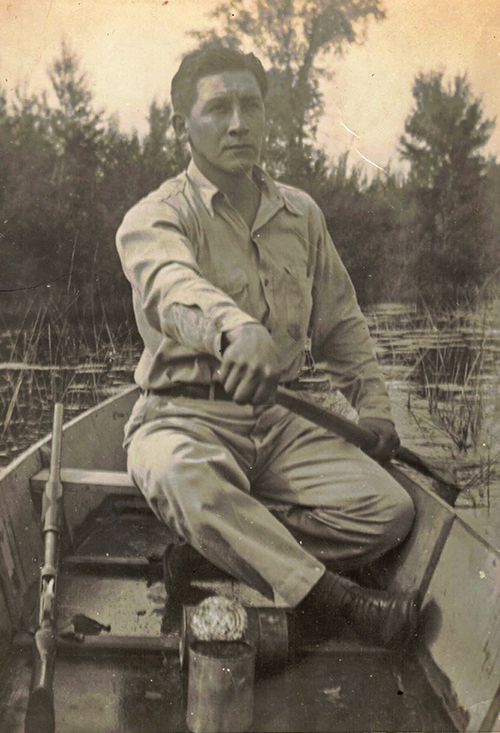

"The Hunter" Jerome, Likely Autum 1942, Bad River Reservation, likely Kakagon sloughs. - Courtesy of Liz Arbuckle

Jerome P. Arbuckle, Bad River tribal member and descendent of the Crane clan, was a storyteller through his songs, beadwork, regalia making, traditional powwow dancing, and writings. He used stories to teach about the land and culture using logic, humor, and artistic flourish.

Arbuckle was born July 20, 1911 in Odanah, Wisconsin on the Bad River Reservation to John Arbuckle (St. Croix) and Sophie Twobirds Arbuckle (Bad River). He was the oldest of six children. He married Grace Morrison and they had two children, Jerry and Joan.

Arbuckle was sent to an Indian boarding school far from his reservation. However, he escaped and walked home to Bad River. That happened twice. Upon his second return, he hid out in the woods with elders who were trying to live a peaceful, traditional life away from federal government and church authorities. Arbuckle stayed with them, hunting for them and chopping their wood. It was from these elders that he learned many traditional songs, stories, land usage ways, beadwork, outfit making, and Ojibwemowin.

Arbuckle loved being out in the woods observing, recording in his journal, hunting, fishing, trapping, and gathering as often as possible. He was an early treaty rights protector. He attended the Hayward Indian Congress of 1934 to meet with federal officials about the proposed Indian Reorganization bill. He said, “If this bill takes away our hunting and fishing rights, it takes away everything from us and will be of no benefit to us. (We should have) jurisdiction over (Bad River’s) navigable waters… (If not,) I would like to know what good our treaty is then.”

In 1935, Arbuckle became a writer for the Work Project Administration’s Indian Research Project on Bad River. He wrote many stories including one on dodaim (totem) or clan:

The Chippewa regarded the animal totem symbol in its natural state with reverence. One old Indian was guiding another man in a boat along the lake shore. They saw a deer run from the woods and plunge into the water. Shortly after the deer had disappeared, a huge timber wolf came to the water’s edge, apparently chasing the deer by scent, for it spent some time sniffing around the water. The man in the bow of the boat raised his rifle to shoot the savage brute. The old Indian promptly intervened, exclaiming sharply, ‘Eh! eh' gigo. Mi ow nin dodaim,’ (Don’t, that is my dodaim).

In the late 1940s, Arbuckle left the reservation to find work, moving his family to Richland, Washington and then on to Long Beach, California. Wherever he went, he sought out a Native community. He attended powwows all over southern California, sharing Ojibwe songs and learning new ones. He sang with a hand drum and with various powwow drums over the years. He made beautiful powwow regalia, including Ojibwe woodland style beadwork, bustles, and head roaches.

He returned to Bad River in the 1970s and picked up where he left off in the tribal community. He was happiest when he was hunting, fishing, trapping, and ricing again and sharing those traditions with his son and grandchildren. He taught some young men on the reservation how to “pound drum” as it was called then, including the songs and traditions. Arbuckle died on July 30, 1991. Today, those men still honor Arbuckle when they sing his old songs.

One story Arbuckle shared was about why Ojibwe people always build their lodges with the entryway facing east. He said, "It’s good to wake up facing the sunrise, preparing you for your day, and saying your prayers." Then he would add, "and it helps keep the wind down because weather usually blows in from the west, you know, the jet stream." He was the best of storytellers, reminding us that stories weren’t just entertainment — they were science and math, history and health. Ojibwe people survived harsh winters, wars, and encroachment because of the knowledge contained in all of these stories.

*This story was written by Liz Arbuckle Bad River Ojibwe, Outreach Specialist, Wisconsin Historical Society