Preserving the Prefabricated Metal Elements on Your Historic Building

Your historic commercial building may have “prefabricated” metal elements. Prefabrication is the practice of assembling structural components in a factory or other manufacturing site and transporting them to the building site. The term “prefabrication” is different than the more conventional construction practice of moving basic materials to a building site where all construction is completed. Prefabricated materials such as pressed metal and cast iron were especially popular for commercial building construction in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

By recognizing the prefabricated components of your commercial building and following best practices for these unique elements, you will be able to preserve this important character-defining feature of your building.

Metal Element Use on Historic Commercial Buildings

Prefabrication was widely employed after 1860 to add cast iron to storefronts and pressed metal to upper facades. During the 19th-century industrial revolution, a variety of new metals were introduced into building construction. Metals that were used at various times for different architectural features include cast iron, steel, pressed tin, copper, aluminum, nickel, bronze, galvanized sheet iron and zinc. These metals were manufactured at industrial sites and transported by rail or ship to Wisconsin’s downtown commercial areas.

Cast-Iron Elements

Cast iron was a popular facade element on commercial storefronts into the early 20th century. Your storefront may have cast iron features such as pilasters or columns. Cast iron was produced in foundries and poured or “cast” into molds. Cast-iron columns and pilasters were used to replace wood columns or brick piers as load-bearing members of the upper masonry wall to maximize the display window area. Cast iron was also used for interior support columns and applied as exterior decorative elements, such as window hood molding. After 1910, most storefronts were built with steel lintels to support the upper facade masonry.

Pressed-Metal Elements

Charles Hornung City Bakery and Restaurant, 1891

Mineral Point, Wisconsin. Recently restored, this is an example of a Mesker pressed metal facade. Source: Photographer Mark Fay. View the property record: AHI 59711

Another prefabricated metal element used as an exterior architectural feature of historic commercial buildings is pressed metal. Materials such as zinc and pressed tin were used because they were quite pliable and could be tool-pressed to create intricate design patterns. The use of pressed tin declined after about 1930.

Pressed tin sheets were applied to storefront surfaces, such as the ceiling of a recessed entrance. These ceilings were often painted white to resemble cast molding. This ceiling treatment was also popular on the interior of buildings. Pressed tin and similar metals were sometimes used as an entire facade covering for the building. Sheets of metal were fabricated into various panels and then attached together to appear as one intact facade. These panels were often quite decorative, with attached columns, floral designs and hood molding over the windows. Sheet metal was widely used in roof cornices; many commercial buildings have cornices with brackets or classical details such as modillion blocks or dentils.

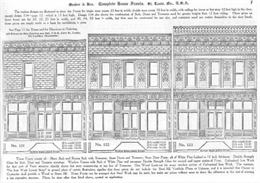

Mesker catalog

St. Louis, MO. As seen on this page from a Mesker Brothers catalog, building owners could select from a variety of storefront designs for installation on their new building.

Like cast iron, sheet metal fronts were produced in factories, shipped to the site and attached to the face of the building. Building owners could order these prefabricated elements from catalogs. Two of the most important producers of cast iron and metal fronts were the George Mesker Company and Mesker Brothers. The designs and materials of these two companies can be found throughout Wisconsin.

Steel and Aluminum Facades

Although prefabricated material use declined for commercial building facades in the early 20th century, it was revived after World War II. After 1945, manufacturers produced entire building facades of steel or aluminum that were installed on new buildings. These sleek exteriors were usually made up of panels assembled together and built on-site. These types of designs were used not only in downtowns but also for buildings constructed along major highways.

Metal-paneled facades were also used to “modernize” older commercial buildings, so many of the original 19th and early 20th century building facades were concealed beneath these added panels. This practice became known as adding a “slipcover” to an older building. The practice was used in an effort to make downtown areas look more modern and to reduce maintenance needs. In recent decades, many historic building owners have removed these slipcovers and restored their buildings’ original, historic facades.

Follow Best Practices

When you are making maintenance and renovation decisions about the prefabricated metal elements on your historic commercial building, follow these best practices:

- Preserve and maintain your original cast iron and pressed metal elements. Metal elements such as cast iron and sheet metal facades are significant features of a historic commercial building that should be preserved and maintained. Do not cover, remove or conceal these elements.

- EnlargeClean metal elements with the gentlest means possible and keep them free of rust. Use appropriate chemical methods to clean soft metals such as bronze, lead, tin and copper. The finish on these metals can be easily damaged with abrasive cleaning methods. You can clean cast iron, wrought iron and steel metals to remove paint buildup and corrosion using hand-scraping and wire brushing. If these methods are not effective, low-pressure dry grit blasting (less than 100 pounds per square inch) may be appropriate.

John Pritzlaff Hardware Company Building, 1875

Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Rust is visible on the upper portions of the cast iron columns. Compare this to the lower portions where the paint is in-tact - no visible rusting. Source: WHS - State Historic Preservation Office. View the property record: AHI 16132

- Refinish bare metals as quickly as possible. When you are applying a new protective finish to any bare iron- or steel-based metal elements, apply the finish quickly. When these metal elements are cleaned and stripped of their finish, they will begin to oxidize in as little as two days. If oxidation occurs, the new finish will not hold as well or last as long. When you are stripping paint from these materials, work in small areas (equal to one day’s work) and move section by section around your building. Strip off the old finish in one small area on the first day, and then repaint the area the next day.

- Repair metal features by patching, splicing or otherwise reinforcing the metal using recommended preservation methods. If your building has extensive deterioration or missing metal elements, restore these elements using limited in-kind replacement with compatible substitute materials. Use a surviving example or find historical documentation of your building to create an accurate reconstruction of an original element. Replicate missing elements with new metal that matches the original metal as closely as possible in texture, profile and appearance. You can also use and substitute materials such as aluminum, wood, plastic, fiberglass and fiberglass-reinforced concrete, and then paint them to match the original. Take care to select a substitute material that is compatible with the original metal and will not cause a galvanic reaction.